A beginning

This is a new blog about the part of eastern England known as the Fens, and the people who inhabit, and have inhabited, the area.

|

| Public Domain |

Who am I? I am an independent journalist who for the last 17 years has published a blog chronicling the “open access movement”. That blog can be viewed here.

At first sight, writing about the Fens may seem very different to writing about a movement dedicated to freeing scholarly papers from subscription paywalls so that publicly funded research is freely available. However, I believe there is a connection.

Open access advocates argue that since research is primarily funded by the taxpayer it should be treated as a commons and made accessible to all. This, they add, was the situation until the end of the last war, when research was primarily published by community-managed and controlled learned societies. Following the founding of Pergamon Press by Robert Maxwell in 1948, however, scholarly papers have increasingly been published by large commercial companies.

This, say open access advocates, has seen research increasingly privatised and exploited by what they characterise as greedy rentier capitalists – for the benefit of shareholders rather than the research community, or the taxpaying public that funds much of the research undertaken. Specifically, they complain, commercial publishers operate a system whereby when they publish research papers authors are required to assign copyright in the work to the publisher, even though the publisher pays nothing for acquiring that intellectual property. The publisher then sells the papers back to the research community in the form of subscriptions to increasingly expensive scholarly journals.

Open access advocates argue that researchers should instead insist on retaining the copyright in their papers and demand that they are distributed with a Creative Commons licence attached. This would allow research to be freely distributed on the internet with no paywall restricting access. Moreover, others would not only be able to read the research for free, but reuse and adapt it too – creating a “circulation of the common”. Essentially, the open access movement wants to see the research community regain control of the publishing process and leverage the internet to recreate the scientific/scholarly commons that it maintains existed previously.

The metaphor of a commons is also widely used by the other open movements that have emerged as a result of the internet, as it is by the broader “commons” movement. These movements could be said to be seeking to return to pre-industrial economic models – specifically, models in which both cultural and natural resources are jointly owned and managed by co-operative communities, rather than being privately owned.

This challenges the capitalist assumption that private property promotes greater efficiency because it encourages the owners of resources to maximise their value. It also challenges the associated belief that private property is the only way of avoiding a tragedy of the commons – i.e. if a resource is made freely available it leads to a free-for-all in which the resource is quickly depleted and so proves unsustainable.

What has helped encourage the open and commons movements is that political economists have begun to question such received opinion, as most notably did the late Nobel prize winner Elinor Ostrom. After studying the interaction of people and their ecosystems in a number of different parts of the world (e.g., by exploring the way pastures are managed in Africa, the way irrigation systems are managed in Nepal, and the way lobster fishing is managed in Maine), Ostrom concluded that even exhaustible resources can be, and are still, managed in a rational way by communities and groups of people without the intervention of either governments or markets, and without the resource in question being depleted. These “common pool resources” are managed on the principle of collective action, trust, and cooperation.

That is, Ostrom maintained

that exhaustible goods (or “rival goods”, where

consumption of the “good” by one person can prevent others from consuming it –

e.g. pasture, food, clothing etc.) can be managed by communities without recourse

to privatisation or state control. Open access advocates argue that a commons

approach is all the more plausible when the resource in question is a non-rival

good (e.g., information). Here one person’s consumption of the good does not prevent

others from consuming it. It also cannot be depleted.

“taking of the commons from the

commoners.”

What has this to do with the Fens? It is this: the land, and the fish and fowl that inhabited the large tracts of open water the Fens contained, were also historically treated as common pool resources and jointly managed by local communities in the manner described by Ostrom. This process has been described in detail by Susan Oosthuizen in her book The Anglo-Saxon Fenland. Oosthuizen explains how local communities in the Fens worked co-operatively to timetable grazing and hay making and to restrict fishing and fowling to particular seasons. The rules determining this were collectively agreed and managed through “fen courts”, and those with common rights were expected to attend and participate in the process. (I shall be publishing an interview with Oosthuizen in the near future).

However, over the past 400 or so years, the Fens have undergone a prolonged process of enclosure and privatisation – much as open access advocates complain that research has been privatised. The history of the Fens, says Professor Ian Rotherham (with whom I shall also be publishing an interview) is essentially one of “the taking of the commons from the commoners.”

This appropriation was achieved by means of draining the Fens (a process that began in the 1600s but not fully completed until WWII) and by privatising the land (notably by means of the Enclosure Acts of the 1700s onwards). Here the capitalists involved were usually referred to as “adventurers”. They provided the money (capital) to build dikes to hold back the sea in order to create new agricultural land, and the capital to construct canals and lodes, and straighten the rivers, in order to discharge inland water into the sea more effectively and quickly. This too allowed new land to be brought into cultivation. In return the adventurers were rewarded with some of the new land, which became their private property.

The end result is that today much of the water that was inherent to the Fenland has been drained and its land removed from common ownership.

No expert

I must note upfront that I am not an expert in the history of the Fens. Nor am I from the Fens. I first came to East Anglia in 1974 to study at the Cambridge College of Arts and Technology (now part of Anglia Ruskin University). Like many students I did not wander very far outside the City. When I did, I noticed that the land towards Ely was rather dark (i.e., peaty) and the landscape pretty flat. But I did not give the matter much thought beyond that.

When I returned to the area in 2016, however, I began reading about the Fens and travelling around the area (although not during the last year, sadly). Having done so, I have come to the conclusion that the history of the Fens raises important questions, not just about the Fens, but about the history of this country, and its politics, its religion and its geography. Above all, I believe the Fens encapsulates the existential dilemma that climate change poses for us all today.

In other words, the history of the Fens inevitably draws our attention to the environmental crisis that mankind faces. And it highlights the harmful trade-offs (and negative externalities) that capitalist modes of production and industrialisation have played in producing that crisis.

But like many things, this is a complicated picture. On one hand, what has been done to the Fens could be presented as an uplifting story of human ingenuity, effective land management and scientific progress. It has seen what many viewed as an unhealthy watery wasteland transformed into one of England’s primary – and particularly fertile – agricultural regions. The draining of the Fens also eradicated the debilitating Fenland Ague that plagued local people for generations.

On the other hand, one could portray it as a shocking story of human short-sightedness, greed and wanton destruction. After all, Ostrom’s research might seem to suggest that there was no real need to privatise, enclose and drain the Fens. This watery world had been feeding and supporting local inhabitants since the end of the ice age. Draining the Fens not only obliterated a traditional way of life based on community ownership and the collective management of natural resources but it destroyed much of the local habitat and the flora and fauna that depended on that habitat. This has played a part in creating the climate change crisis we now face.

Over the long term it has also proved to be a counter-productive strategy, not least because, when it dries, the peat that makes up a great deal of the Fens shrinks, causing the land to sink. For an area that was never much more than 10 metres above sea level this is not good news.

In addition, when the peat and silt of the Fens dries the soil begins to decay and blow away, giving rise to “Fen Blows” – essentially, dust storms. That the landscape of the Fens is flat and generally unwooded makes these events both more likely and more damaging. This has doubtless also played a role in the sinking of the Fens, and presumably continues to do so – a process that the famous Holme Fen Posts vividly demonstrate. Holme Fen is now said to be the lowest land point in Great Britain, at 2.75 metres below sea level.

With many parts of the Fens now below mean sea level, the rivers, lodes and canals intended to drain the area are today higher than the surrounding land. To keep it sufficiently dry, therefore, water has to be pumped uphill before it can drain away. And as sea levels rise so it is necessary to build ever higher and stronger sea walls to prevent the land being flooded by the sea. The more the Fens fall, and the more the North Sea rises, the more expensive the task of keeping the area drained becomes. At what point does the task become too expensive and/or difficult?

All in all, I believe the Fens has something important to teach the world. As a result of their draining, and hundreds of years of peat extraction, they have played their part in causing climate change. But could they not become part of the solution? After all, peat is a highly effective natural carbon sink. Rather than further drying and depleting peat bogs is it not time to restore them? This, as it happens, is the aim of the Great Fen Project in Cambridgeshire. And rather than continuing to try clawing more and more land from the Wash is it not time to return some of the drained land back to the sea, or use it to create new marshes to provide natural habitats for threatened wildlife – as, by the way, is being done at Freiston Shore in Lincolnshire.

However, even if Ostrom’s analysis is accepted, and projects like the Great Fen continue, we have to wonder whether what has been lost can ever be adequately recovered. A question that inevitably arises with both the Fens and the various open movements is whether, and to what extent, a commons can be reinstated once it has been privatised and/or destroyed. Personally, I believe the open access movement has failed (to date at least) – as I have detailed here. Whether it can be adequately reinstated in the Fens has yet to be established.

But if mankind is

to tackle climate change in order to survive we are surely going to need to move

to a post-industrial society and develop post-industrial economic models, and to

do so with some haste. The implications of not doing so would appear to be dire,

not just for the Fens but for the entire planet.

Nursery

In reading up on the Fens one also quickly discovers that the area has been the nursery for some fascinating people, and the location of some significant historical events, not least the final chapter of Saxon resistance to the Norman Conquest – a showdown that took place on the Isle of Ely in 1071 and was led by legendary Lincolnshire-born Hereward the Wake. Ely (and its striking cathedral) has over the years been at the centre of other important events too of course, including the 1816 Special Commission assizes that tried the Littleport rioters and sentenced five of them to death.

For its part, Huntingdon was the birthplace of Oliver Cromwell, the erstwhile farmer and landowner who went on to lead the armies of the Parliament against King Charles I during the English Civil War, and later became Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland. Cromwell’s military prowess began perhaps with his recruitment of a cavalry troop in Cambridgeshire and his subsequent successful military actions in East Anglia in 1643. Cromwell was also instrumental in the creation of the country’s first national army, the New Model Army.

Elsewhere, Wisbech has been the birthplace of some interesting people too, including Octavia Hill, the social reformer and co-founder of the National Trust, and Thomas Clarkson, the abolitionist, and a leading campaigner against the slave trade in the British Empire.

And King’s Lynn was the birthplace of English satirical novelist, diarist and playwright Fanny Burney as well as of Robert Armin, the English actor and member of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. Armin became the leading comedy actor with the troupe associated with William Shakespeare following the departure of Will Kempe around 1600.

Meanwhile, the list of notable people born in Boston is long, and includes the 16th Century historian John Foxe, the founder of the Illustrated London News, Herbert Ingram and, more recently, the actress Amanda Drew, who played Dr May Wright in the soap opera EastEnders.

In reading and thinking about the Fens what has most intrigued me, however, is that it is very difficult to get a clear idea of what the landscape looked like before the drainage began. As Ian Rotherham points out (in the Q&A I will publish with him shortly), much of this took place “prior to the availability of prints etc.” And for obvious reasons there are no photographs.

What it would have been like to live in and travel through the Fens prior to the draining, therefore, is not easy to envisage. We have some accounts from diarists Samuel Pepys (1662) and John Evelyn (1670), and from the English traveller and writer Celia Fiennes (1695) and writer, journalist and pamphleteer Daniel Defoe (1724). But it is hard to get a good mental picture. Nor, it seems, is it easy to say precisely where the boundaries of the Fens are: this appears to be dependent on what historical point you take. And with Fenland rivers having been re-routed many times over the years, it can be a struggle to establish where some of the old river courses were (see here, for instance). All of this gives the area a certain romance, not to say an aura of mystery.

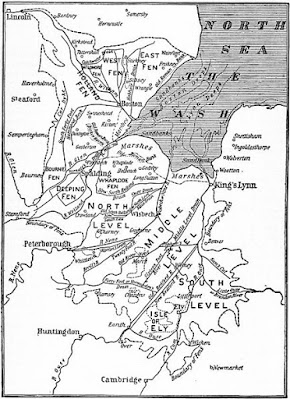

That said, one image I find striking is the 1648 map produced by the Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu called (tellingly) Regiones Inundatae. The section I include here gives us a sense of just how much of the area was underwater and/or subject to regular flooding, with towns located on “islands” and lakes or “meres” dotted across the landscape, including the famous Whittlesey Mere – said to have been 3 miles broad and six miles long in 1697. (See also this from 1648).

Journey of discovery

In short, the history of the Fens has a beguiling mystique. What cannot be doubted, however, is that the area has over time experienced some momentous changes, not least man-made changes that often proved catastrophic for local inhabitants. Many communities that had for generations lived in symbiosis with the watery fen landscape, and were dependent on its abundance of eels, fish and fowl, along with the willows, peat, reeds, rushes and sedge that were so plentiful, found themselves impoverished, side-lined, dispossessed and deracinated.

It is this long process of change, and the experiences of those who have both profited and suffered from the changes, that I want to explore in this blog – along with all the other people who have lived in and enjoyed the Fens over the years.

Following the example of James Boyce in his book Imperial Mud: The Fight for the Fens, by the way, I plan to use the term Fennish to describe the people of the area.

However, I don’t want to paint too backward-looking a picture. I am also interested in the events, places and people of the Fens today and suggestions for topics I could look at and explore are welcomed. I am particularly interested in stories of continuity, and so pointers to families who have lived and worked in the Fens for generations, and businesses that have survived the swings and roundabouts of changing times, would be greatly appreciated.

|

| Priory Farm, Burwell today |

Finally, I am especially interested in the future of the Fens. In saying this, I am all too conscious that in his 2019 book The Fens, archaeologist Francis Pryor included an epilogue called “Farewell to Boston” in which he painted a scenario that will likely horrify many, but might be welcomed by some. Pryor suggests that the Fens will inevitably have to succumb to water again in some way, at some point. This could be by means of a series of dramatic inundations, or preferably as part of a process of a managed retreat.

In other words, as the sea continues to rise and the land continues to fall it will not be possible to keep all parts of the Fens dry. As Pryor puts it, “[I]t’s a process that cannot be delayed forever. We can go on raising sea walls, but eventually the waves must break through them.” In fact, he says, the process of retreat has already begun – at Freiston Shore, for instance.

If such a process does take place, Pryor adds, “I fear that Boston and Spalding would fare badly, as would Fengate and much of eastern Peterborough … Sadly, the beautiful town of Wisbech would be an early casualty.”

In short, the history of the Fens is by no means over, and further big changes seem inevitable.

I will end by repeating that I am not expert on the topic of this blog. For me, the project is a journey of discovery. To bring some expertise to that journey I plan to kick things off by interviewing some specialists.

First up will be Ian Rotherham, who researches environmental, historical and tourism issues around the world, and who authored the book The Lost Fens: England’s Greatest Ecological Disaster. A Q&A with Ian will be forthcoming in the next day or so (now published here).

This will be

followed by an interview with Susan Oosthuizen (now published here).

Comments

Your writing is beautiful. The analogy between the Fens and open access, using the conceit (concept?) of the Commons, is perfect.

Jeffrey Beall's story is a sad and unfortunate one. Anyone who is curious to learn about it can read this Nature story, or the Wikipedia page on him.

I interviewed Beall in 2012. This can be read here.