Wicken: A fenland village

On a sunny March day earlier this year I turned off the main Cambridge/Ely road (A10) at Stretham and headed down the A1123 towards the village of Wicken. I was looking for Wicken’s parish church, St Lawrence’s, which, I had read, is a 14th Century church with a 13th Century chancel.

It was not until I had driven all the way through to the other side of the village that I found the church, which turns out to be the very last building on the very last corner as you leave Wicken. Once you pass it, you are catapulted back out into the flat fen landscape and find yourself rushing towards Fordham.Managing to come to a halt before I was thus catapulted, I was rewarded with the sight of a fine-looking church set within an appealing landscape and silhouetted against a beautiful sunny sky. “For all that,” I muttered to myself, “the church is surely on the wrong side of the village.”

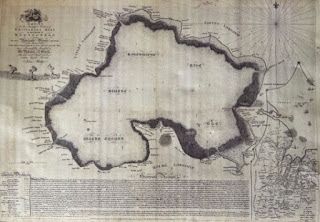

However, when I returned home and looked at the Regiones Inundatae map produced by the Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu in 1648 (below) the church’s location on the very eastern edge of the village made a little more sense to me.

As the map suggests, before the Fens were drained Wicken was essentially a peninsula into the marshes and bogs that were once so prevalent in this part of the country, and the only land route into the village was from the East. Viewed from this perspective, the church was probably the first rather than the last building visitors encountered historically.In fact, it was not just marshland that prohibited access to Wicken from the West. There are also two rivers that run between the village and the A10 (for centuries a major road between London and King’s Lynn): the river Cam and the Great Ouse (also known as the “Old West”). These don’t merge into one river until Pope’s Corner, about five miles North of Wicken.

Nevertheless, the village’s centre of gravity has moved West over time – as Wikipedia points out: “The newer centre of the village is now some distance away [from the church]”.

One reason for this shift, perhaps, is that the only other way into Wicken prior to the Fens being drained was by water – either via Soham Mere (which, until it was drained in the late 18th century, consisted of over 1,000 acres of water) – or travelling by boat through Wicken Lode, a branch of the Burwell Lode that joins the river Cam at Upware. The Blaeu map might seem to suggest that people arriving by water would have disembarked somewhere in the centre of the village. But this is speculation on my part.

A further possible reason why a land route into Wicken from the a10 was so long coming is that in the 19th Century a railway (the Fen Line) linking Cambridge to King’s Lynn was constructed and runs between the two rivers as it passes Wicken. While there is today an unmanned level crossing over the line, perhaps the railway was viewed as a third obstacle to creating a public road to Stretham. Ironically, I am not aware that a station was ever built to serve the village.

Nevertheless, I find it striking that permanent bridges over the two rivers between Wicken and the A10 were not built until 1928. All of which reminds us just how isolated many parts of the Fens were historically.

Henry Cromwell

But my initial motivation for visiting Wicken was not an interest in its geography or its transportation routes but in one of the village’s more famous inhabitants – Henry Cromwell. The fourth son of Oliver Cromwell, Henry retired as Lord Deputy of Ireland at the time of The Restoration (1660). At that point he took up residence in a former priory called Spinney Abbey, which is located on the western side of Wicken.

Henry and his wife are buried in St Lawrence’s, and there is in the church both a brass plate and a memorial slab (below) in memory of Cromwell.

The initial purpose of my visit was to track down these memorials. The obstacle I immediately faced was that, as a result of Covid-19, the church was locked up.By a strange coincidence, it turned out that Fuller himself now lives in Spinney Abbey (although not in the original building).

The two booklets I obtained from him contained some fascinating information about the history of the village, of the church, and of Spinney Abbey. This has served both to broaden and deepen my interest in Wicken, and indeed in nearby Wicken Fen, one of the few remaining fragments of wild fen in Cambridgeshire (which I had visited on a number of occasions previously).

Drainage

As one might expect of any history of a Fen village, the topic of drainage features strongly in the church booklet. This has always been a controversial topic and is today very much viewed as having been a mixed blessing. It improved transport routes, increased local people’s access to the outside world, and allowed a large amount of fertile land that was previously waterlogged to be brought into cultivation.

On the other hand, it saw land that had previously been owned and managed by the local community privatised and enclosed, and the abundant quantities of fish and fowl that the wetlands had supported (and that had sustained local people from time immemorial) significantly depleted. Over time there has been substantial loss of wildlife and plant species.

Draining has also had a long-term negative impact on the environment. And what had not been fully appreciated, it seems, is the extent to which reclaimed fenland sinks. Amongst other things, this has made the Fens more susceptible to periodic (and sometimes catastrophic) flooding.

It is not clear to me how much land was privatised as a result of the marshes and meres around Wicken being drained. Nevertheless, I assume the process would inevitably have deprived local people of free food and resources, and thus of agency. Certainly, the process was resisted by ordinary folk in Wicken, who expressed their opposition by attacking nearby drainage works and rioting.

However, we might not want to portray this as a simple rich versus poor, or class, issue. In Wicken both the local justice of the peace Isaac Barrow and his son-in-law, the curate of Wicken, Robert Grymer were sympathetic to those who fought the drainage process. (An earlier inhabitant of Spinney Abbey, Barrow was the grandfather of his namesake Isaac Barrow, a talented mathematician and tutor to Isaac Newton).

In 1638, two “messengers” arrived in Wicken to arrest the leader of the local rioters, John Mortlock. Perhaps not accidentally, they turned up when Barrow was away in London. Either way, as often happened in the Fens when the authorities intervened, the messengers were greeted with pitchforks and ridicule. And since Grymer refused to intervene, they eventually had to leave empty handed. Doubtless to their further chagrin, their departure was celebrated by a crowd of aggressive women shouting insults and a group of men on top of the church threatening them with piles of stones.

As elsewhere, however, the “adventurers” eventually got their way, and most of the wetland around Wicken was drained. One notable exception was Wicken Fen (which I assume is a small remaining portion of what the Blaeu map refers to as Burwell Fen). This remains wet to this day and supports an abundance of wildlife. Indeed, it is now one of Europe’s most important wetlands, and protected by the designation of being a Ramsar wetland site of international importance.

Wicken Fen’s long survival surely also owes much to the National Trust (which first began to care for the site in 1899) and to the banker and entomologist Charles Rothschild, who in 1901 purchased the first parcel of land that makes up Wicken Fen today.

Spinney

Abbey

For its part, Spinney Abbey began life as a 13th Century Augustinian priory called Spinney Priory. Originally an independent institution, it was later absorbed into the cathedral priory of Ely, and then dissolved by Henry VIII in the 16th Century. At this point it seems to have been renamed Spinney Abbey and became a private dwelling. Henry Cromwell occupied the property from 1661 until his death in 1674.

At some point after Cromwell’s residency, the original building was destroyed, and in 1775 a new house was built with parts of the demolished building incorporated into it. The owner at this time was Charlotte, Countess of Aylesford.

In 1892 both Spinney Abbey and the land surrounding it were leased by a farmer called Thomas Fuller. The Fullers were a local family who had been farming in adjacent Padney since at least 1695.Today

Today it is Robert Fuller and his wife Valerie who live in the house, while their son, Jonathan Fuller, runs the farm. This includes a traditional beef herd of English Longhorn cattle and Gloucester Old Spot pigs.

The farm prides itself on the quality of its grazing land and has been part of the countryside stewardship scheme since 2004.There is also a farm shop that sells traditional breed meats and craft cider. The latter includes varieties with de rigueur names like “Monk & Disorderly”, “Virgin on the Ridiculous”, “Fruity Friar”, and “Dirty Habit”.

I took advantage of my visit to purchase some sausages from the farm shop, and very tasty they were too!Tomorrow

My visit to the village has left me wondering if Wicken should be viewed as an archetypical Fen village or whether it is distinctive in some way. Unfortunately, I am not sufficiently knowledgeable to answer that question with confidence. Certainly, other Fen villages have their own distinctive and interesting histories: Aldreth, for instance, is said to have been the site of two battles between Hereward the Wake and William the Conqueror.

Nor is Wicken Fen the only fragment of wild fenland remaining in Cambridgeshire. There is also Chippenham Fen, Woodwalton Fen, Holme Fen and Fordham Woods, for instance. On the other hand, Wicken Fen (and thus the village) has acquired a particularly high profile nationally, presumably as a result of successful marketing by The National Trust.

Wicken is likewise not the only place where fenland has been restored. During WWII Adventurers Fen (which adjoins Wicken Fen and previously I assume also part of what the Blaeu map denotes as Burwell Fen) was requisitioned for agricultural purposes and drained. After the war it was returned to the National Trust with the stated intention of reflooding half of it. Today I assume it is incorporated into Wicken Fen.

We are seeing efforts to restore, extend, and rewet former fenland elsewhere too, with a number of such projects underway. As part of the Great Fen Project, for instance, farmland is being purchased and turned back into traditional Fen landscape. It is also intended to connect Woodwalton Fen and Holme Fen to create one continuous site.

There have also been reports that environmentalists want to resurrect the lost lake of Whittlesey Mere – a stretch of water north of Holme said at one point to have been three miles broad and six miles long.

(See the chart of Whittlesea Mere produced by John Bodger in 1786).

The story published in The Times in 2019 that asserted this may have succumbed to journalistic hyperbole but it draws our attention to the possibility that restoring fenland to its original state could prove controversial and face increasing opposition.

Weeds and foxes

Some locals, for instance, complain that restoring land to wild fen simply makes it a “haven for weeds and foxes”. Speaking to The Times, a former tenant farmer whose land was sold to the Great Fen Project said: “It’s a disaster. Predators like foxes, badgers and buzzards are back but they are killing the ground-nesting birds.”

We have also seen concerns expressed that rewetting will see a return of the Fenland Ague (also known as Marsh Fever), a mild form of malaria that (some say) was responsible for the death of Oliver Cromwell at the early age of 59.

Concerns like these are not new. When in 1953 politicians learned that Adventurers Fen was to be handed back to the National Trust and reflooded, for instance, questions were raised in the House of Commons.

But as new and more ambitious projects get underway should we not expect to see ever greater pushback?

Environmentalists are understandably keen to assuage public anxiety. Apart from being essential for wildlife conservation and the preservation of natural habitats, they argue, rewetting and rewilding fenland is a more effective long-term response to climate change and rising sea levels than throwing ever greater sums of money into raising drainage embankments, strengthening sea walls and developing ever more expensive flood mitigation schemes intended to protect the status quo. Unless a more realistic long-term approach is taken, they say, such schemes are likely to prove unsuccessful in the long run and counter-productive.

In other words, we may have no choice but to restore and/or rewet more areas of the Fens and to engage in coastal “managed realignment” schemes like that being undertaken at Freiston Shore.

But as organisations like the National Trust and Natural England set about increasing and extending their fen restoration programs, as more farm land is taken out of production to do so, and as new managed realignment projects are begun and start to return reclaimed land to the sea, is there not a danger that the process will become as divisive as the draining of the Fens was in the 17th Century?

The secret to success for those organisations engaging in such schemes will surely lie in communicating effectively with the public: explaining why the schemes are necessary and outlining the long-term benefits they will bring. While practitioners and researchers show strong support for these approaches local communities tend to view them in a negative light.

In short, my March visit to St Lawrence’s church to track down two memorials to Henry Cromwell ended up making me curious not just about the history of Wicken but also its future, and indeed the future of the Fens more generally.

Postscript: On 13th May, a report jointly authored by the Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire was released aimed at providing a systematic approach “to bring about nature’s recovery” in and around Cambridge. In the report, Wicken Fen is earmarked as one of the areas for expansion. The report notes that the National Trust has acquired land adjacent to Anglesey Abbey and that its landscape vision is to “connect Wicken Fen to Cambridge”. More information is available in this Cambridge News story.

Further reading:

Spinney Abbey

Wicken,

Michael Rouse, 1991

Wicken and its Church, Anthony Day, 1996

Comments