Q&A with John Badley, Senior Site Manager at Freiston Shore nature reserve

Managed realignment is the deliberate process of altering flood defences so that land that had previously been claimed from the sea is returned to it by re-flooding.

The strategy is driven by two

main factors: 1) environmental legislation aimed at preventing

the loss and degradation of coastal habitats, and the animal and plant life

that depend on those habitats, and 2) the need to reduce the flood and erosion

risk to people and property as climate change causes sea levels to rise.

Importantly, it also holds out the possibility of being a more cost-effective way of

reducing flood risk.

The strategy is relatively new but has in recent years

been undertaken at a number of sites around the UK, including Medmerry

in Sussex, and Abbotts

Hall,

Alkborough

Flats and Freiston

Shore in Lincolnshire.

The interview below with the RSPB’s John Badley is about

Freiston Shore nature reserve and the managed realignment project that enabled the

reserve to be created. When the project was embarked on it was the

largest managed realignment scheme to date.

In the 1880s, however, the sandy beach that had

attracted so many visitors slowly began to disappear, as the saltmarsh

surrounding the area started to spread. Freiston Shore’s popularity and tourist numbers

declined accordingly.

In the next period of its history, Freiston Shore became one of the areas in Lincolnshire where land was claimed from The Wash. This occurred from the 1940s and

ended around 1983, when Freiston Shore became one of the last projects to claim land from the sea. Specifically, HMP North Sea Camp prison built an outer sea bank as an extension to one that had been built in the

middle of the century with the aim of creating new agricultural land.

More cost-effective solution

Unfortunately, the new outer sea bank was built in a

place that was vulnerable to storm tides and so had to be regularly repaired,

which had obvious cost implications. In 1999, therefore, it was decided that retreat

was advisable and that the newly claimed land should be returned to the sea.

To this end, it was decided to break the newer sea bank in three

places to allow seawater to flow back in and allow new marshland to form.

While breaking sea banks might seem likely to increase

the threat of floods what has been learned is that marshland can create an effective cushion between the open sea

and land.

In other words, saltmarshes act as natural buffers against the destructive power of the sea – especially in storm surge conditions – as they dramatically reduce wave height and wave action. This helps reduce flood risk. Marshland also prevents soil erosion and sequesters large quantities of carbon.

Prior to the realignment work being approved a cost/benefit assessment was undertaken. This concluded that the proposed work would provide a more cost-effective approach to managing flood risk than constantly

having to improve existing flood defences.

There were nevertheless costs, of course, and a document

produced after the scheme was completed (Managed realignment for people and

wildlife – the Freiston Shore experience) explains how the project was funded.

First, the capital (mainly engineering) costs for the

realignment (£1.98 M) were met from the Environment Agency’s flood defence

budget plus £850,000 funding from DEFRA (75%) and Lincolnshire Flood Defence

committee (25%).

Second, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

(RSPB)

agreed to purchase 92 ha of land from HMP for £150,000. The purchase (which included

the proposed realignment area) has allowed the RSPB to create the new nature reserve at Freiston Shore,

with the costs met by using income from a donation made to the RSPB by the

McLellan Trust in memory of the late Barbara McLellan.

Unforeseen consequence

Once the initial engineering work was completed (in

2002) management of the site was handed over to the RSPB to allow them to create

the new reserve. Material that had been dug out to strengthen the old bank was

used to create a large lagoon as an attractive habitat for wading bird

populations. The creek system that had existed prior to building the new sea wall was also rebuilt, and new pools added to

aid tidal flow/siltation and the colonisation of saltmarsh species.

Unfortunately, there was an unforeseen consequence of the work: the

new realignment disturbed the surrounding area of intertidal

habitat in a way that impacted on a local oyster fisherman, who had to be paid compensation

for the negative effect on his business. This was expected to cost several

£100,000’s.

However, while this unanticipated cost might have

altered the result of the cost/benefit analysis had it been factored in, the above

cited report notes: “the realignment remains the preferred and most sustainable

flood defence option, and has significant environmental benefits which are not

given monetary values in the cost:benefit analysis.”

An important point here is that saltmarsh and

intertidal habitats not only reduce flood risk but they are some of the rarest

habitats in the UK and can support important flora and fauna. Yet they have

been disappearing rapidly in recent years. Before it was integrated with Natural England in 2006, therefore, English Nature had

set a target for the creation of 100 ha of saltmarsh per year in England.

The bottom line: while managed realignment can offer a more cost-effective solution to reducing flood risk than constantly reinforcing sea defences, it should not be viewed as a simple cost-accounting exercise.

Either way, for the Fens flooding is a serious issue. With concern growing that urban areas as distant from The Wash as Cambridge could at some point find parts of their town underwater it seems clear that, if flooding is to be avoided in the future, then new and more innovative approaches to reducing flood risk are essential.

The Q&A below with John Badley took place by email

and has been edited for length and clarity.

The interview begins …

|

| John Badley |

A: I’m the Senior Site

Manager for the RSPB overseeing the management of Frampton

Marsh and Freiston Shore nature reserves. I’ve been in

working here since 2000.

Prior to that I worked at Langstone Harbour

in Hampshire and Dungeness

in Kent following a degree in Environmental Studies at the University of London.

Q: As I understand it, the managed

realignment scheme at Freiston Shore is intended

to address a number of issues including, 1) the threat that climate change and

rising sea levels pose for the area in terms of flooding and, 2) the loss and damage

to flora and fauna the area has seen as a result of a decline in saltmarsh and

intertidal habitats. Is that right?

A: Yes. Economics was a big

part too. The Environment Agency [EA]

carried out a cost benefit analysis which concluded protecting the area that is

now the managed realignment was not economically justifiable.

Q: Can you say more about the threats and how

it is hoped that realignment will mitigate them? Removing sea defences to

address problems of flooding might seem counterintuitive to many.

A: Research shows that sea

banks with saltmarshes fronting them are more sustainable and cheaper to

maintain, while also providing valuable wildlife habitat. At Freiston Shore, it

was a case of moving the sea defences back to where they were previously so a

natural saltmarsh can re-establish in front of them rather than removing them

entirely.

It’s important to remember The Wash used to be much

more extensive and is artificially constrained so it’s a case of redressing the

balance and working with nature and natural processes rather than trying to

fight them.

Sea levels are rising and so it appears is the

frequency of storm events, both can have significant impacts on sea banks as

well as the natural habitats in The Wash and the species that depend on them.

The threats include the flooding of homes, businesses

and agricultural land as well as the loss of valuable wildlife habitat. The

realignment mitigates for all these by making the sea defences more viable and

providing wildlife habitat, so it’s a win:win.

Interesting history

Q: Freiston Shore has an interesting

history. Wikipedia notes that

in the late 18th and 19th centuries it had a sandy shore

and was developed as a resort where people bathed and organised horse races and other attractions were provided on the beach. It also had several hotels. This

changed when the sand gave way to saltmarsh. Was that change a result of human

activity or natural processes?

A: Natural processes.

Q: Subsequently, North Sea Camp Prison enclosed

some of the marsh to use as agricultural land. As you noted, this has now been

reversed with the realignment programme. As part of this project the sea bank has

been broken to allow the sea back in and the area has been “landscaped” to make

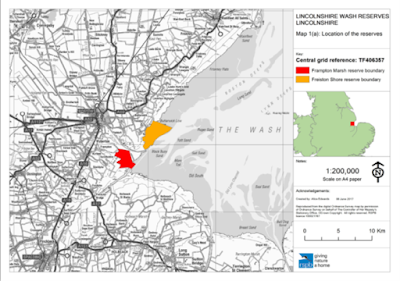

it more amenable to birds and plans. A map I saw online indicates that in

addition to an area designated as management realignment there is a lagoon and

an area of wetland. Can you say what the aim of each section is and what it is

hoped each will achieve?

A: The

lagoon was one of two ‘borrow

pits’

which is where the material was sourced to create the new section of bank and

to provide the material required to raise the existing defences.

This has worked well, and the lagoon has been home to

large numbers of roosting waders at high tide (up to 10,000), breeding birds

(including 1,500 pairs of black-headed gulls and up to 150 pairs of common

terns) and feeding birds (2,000 wigeon and 1,500 brent geese).

In addition, landscaping of the managed realignment

area by adding creeks and pools has provided additional opportunities for

nesting redshank as well as feeding areas for avocets and other waders.

Q: What are the primary birds and plants that

are expected to prosper at Freiston Shore as a result of the project? Do you

expect to see some return that had disappeared from the area?

A: As above, plus saltmarsh

plants, many of which are nationally scarce. The lagoon has already led to the

return of some breeding species lost to the area such as black-headed gull,

common tern, oystercatcher and ringed plover.

Other species have benefitted from additional

opportunities to increase their populations, such as redshanks.

Q: I read that Freiston Shore was the

largest realignment area created to date in the UK.

How much land is involved and what is distinctive about the project aside from

its scale?

A: 66ha.

It is no longer the largest, although it was when it was created in 2002.

Costs

Q: How was the work to create the site

funded and how will the ongoing costs be met going forward?

A: The Environment Agency

paid the costs for the flood defence scheme. And EA are still responsible for

the longer-term flood defence.

RSPB helped facilitate the project by offering to buy

the land from HMP North Sea Camp prison. The cost for this was set by a

District Valuation. RSPB covers the ongoing infrastructure costs (grazing,

benches, footpaths etc.) and habitat management.

Q: Aside from government funding, what

income does the site have to support it going forward?

A: As I say, the flood

defences are maintained by the EA. The management costs for the infrastructure

for visitors and wildlife habitats are paid for by RSPB with funding support from

Natural England’s Countryside

Stewardship scheme.

We ask non-member visitors to pay a £1 facilities fee

covering parking etc. which also helps contribute towards the management costs.

Q: I believe the site has become a tourist

spot. How many visitors are there annually?

A: Around 30,000 per annum,

which is more than we expected.

Q: Is it important that members of the

public visit the site? If so, why? Are there downsides to providing public

access?

A: We want to inspire

people about nature so access for visitors is very important to us. We need to

manage the balance between visitors and wildlife carefully to reduce the risk

of people impacting on the wildlife they come to see.

This is done by providing sanctuary areas for wildlife

and carefully designing access routes etc. There are always issues with open public

access, but the vast majority of our visitors do not cause any problems for us

or wildlife.

Lessons learned

A: An unexpected cost was

the impact the realignment had on an oyster fishery. The owner was therefore compensated

for the unforeseen impact on his business, which was a result of the

hydrological modelling not predicting changes very far outside the realignment

area in The Wash.

The number of visitors was a pleasant surprise, it

just shows that if you provide somewhere nice to enjoy the coast and nature

people will come.

As far as the realignment goes the saltmarsh

established as expected and provided the benefits intended (for flood defence

and wildlife), so that worked as well as anticipated.

Q: I think the concept of managed

realignment is relatively new and perhaps not always understood or welcomed by

the public. A report produced by CoastAdapt

in Australia that looked at three coastal realignment projects in the UK made this

point: “while practitioners and researchers

show strong support for this strategy, the community is more negative. People

tend to assume that defensive structures offer more reliable protection and so

removal of such structures raises community concern and conflict. Public

opinion also depends on local context as well as who pays for managed realignment,

perceived winners and losers from the strategy, and cultural values.” I believe

there was some resistance locally at Freiston Shore but that these objections

were overruled by the local authority. How important is it to try and get the

buy in of local people when undertaking such schemes and what is the best way

of doing that in your view?

A: It is very important.

Local people were generally supportive because many could remember when the

area was a saltmarsh, which it was until it was claimed for agriculture in 1982.

So, it was just 20 years since it had been taken from the sea.

I think where this isn’t the case (i.e., where there

are much older historical land claims) it will be more of an issue. As there

are more examples of these types of schemes it will no doubt get less

contentious and easier to show how it works and provide evidence that there is

better rather than worse flood protection as a result of allowing some land to

be reflooded.

The other benefits – such as the provision of a public

amenity/recreation for walkers and bird watchers, for exercise and wellbeing etc.,

and the local economy benefits from a tourist attraction that brings people to

the area – will help local communities see realignments as beneficial to their

community.

Different needs and expectations

Q: Do you think the different needs and

expectations of different groups of people could see managed realignment and

other rewetting schemes become a source of conflict in the future?

A: Potentially, but if they

are well planned and designed they can deliver multiple benefits. For

conservationists realignments can be a mixed blessing as often the area you

want to realign over is already designated for its freshwater wetland habitats

(e.g. along the Suffolk and Norfolk coasts), so you then need to find a

replacement for that as well.

From a purely nature conservation perspective The Wash

hinterland is not problematic for managed realignment because it is almost

entirely arable, which provides limited complementary/additional value to The

Wash (and unlike saltmarsh, which is quite a rare habitat in the UK and

globally, it’s not in particularly short supply).

Hopefully with the new Environmental

Land Management Scheme being developed in which farmers and

landowners will be paid for delivering public good there will be additional

opportunities for creating complementary habitats that will provide flood

defence, carbon sequestration, tourism, recreation and wildlife benefits.

This may lead to more opportunities and greater uptake

by landowners than is currently the case.

Q: Thinking more broadly: most people who

write about the Fens today seem to deprecate the fact that the area was drained,

or imply that it should not have been drained to the extent it has been. In

reality, of course, things are rarely black and white. I wonder what in your

view are the pros and cons of the Fens having been drained? Is the current

situation sustainable without some radical change of thinking and new

approaches?

A: I understand the reasons

why it was done, but as an environmentalist I think the loss of the Fens as an

ecosystem was a huge shame because we lost one of the most impressive habitats

and landscapes in England.

As for the second question, well, we’re losing peat at

quite a rate, so there is an argument to suggest that current farming methods

are not sustainable in the long term.

Q: What are the pros and cons of land

having been reclaimed from

the sea historically?

A: The pros are that more

land became available for food production, which increased the size of land

holdings/estates. The cons are that it has increased flood risk, led to loss of

wildlife habitat and increased costs plus loss of carbon etc. The word

‘reclaimed’ is often misleading. It usually wasn’t ours in the first place, so

in most cases the land was claimed not reclaimed from the sea.

Q: If we are now having to return some of the

land to the sea does that mean we went too far historically, or is it rather

that the situation has changed?

A: Perhaps both.

Q: What do you think the implications of

climate change are for the Fens overall, both in the short and the long term?

In his book, The

Fens, Discovering England’s Ancient Depths Francis

Pryor included an epilogue entitled “Farewell Boston.” In that epilogue, he said

he had concluded that it is inevitable that the Fens will flood again. As he

put it, “it’s a process that cannot be delayed forever”. He went on to suggest

that Boston, Spalding and Wisbech, as well as Fengate and much of eastern

Peterborough, were particularly vulnerable. Do you agree? If so, what are the

implications of this threat for those who live in the Fens, especially those in

the lowest lying areas? Does it imply that we are going to have to undertake a

lot more coastal realignment in coming years?

A: I suppose it depends on

what timescales we’re talking about and what, if anything, we can do about sea

level rise. We can spend a lot of money building bigger and bigger sea banks,

but, at some point, this may become too expensive or technically unfeasible.

There may come a point when economics wins the argument,

and some areas will be allowed to revert to intertidal habitats. We also have a

moral (and legal) obligation to protect our important wildlife habitats and if

these are being lost to ‘coastal

squeeze’ then we’ll have to find somewhere to recreate these

too.

Q: Thank you for taking the time to answer

my questions.

Comments